Articles

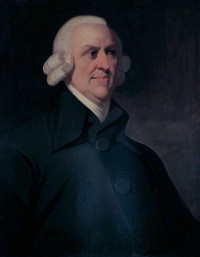

Adam Smith and the Invisible Hand, by

Edmund A. Opitz,

The Freeman, Jun 1976

Explains mercantilism, the rationales for political power, government's proper role, Smith's "invisible hand" metaphor, his concept of "equality, liberty and justice" and how a free society allocates economic goods; based on a lecture given 17 Feb 1976

Smith had made a name for himself with ... Theory of the Moral Sentiments, published in 1759, but he is now remembered mainly for his Wealth of Nations, on which he labored for ten years ... Adam Smith liked this metaphor of "an invisible hand" and used it in Theory of the Moral Sentiments as well as in The Wealth of Nations ... The Wealth of Nations is generally regarded as a work on economics, but Smith did not think of himself as an economist. Smith was a professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, where he lectured on ethics, rhetoric, jurisprudence, and political economy.

Adam Smith - Hero of the Day,

The Daily Objectivist, 2000

Biographical profile published by

The Daily Objectivist

Adam Smith, a major figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, was a self-taught professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow. His work on a theory of 'moral sentiments' preceded and informed his far more influential thinking on economics. Smith argued that the most productive social system is one in which, with few exceptions, individuals are free to pursue their economic interest.

Adam Smith—"I had almost forgot that I was the author of the inquiry concerning The Wealth of Nations", by

Jim Powell,

The Freeman, Mar 1995

Biographical essay

Before Adam Smith, it seemed that most people believed government was necessary to make an economy work ... Adam Smith defied all this with The Wealth of Nations, a clarion call for economic liberty. Although many specifics weren't original with Smith, he created a bold vision which inspired people everywhere. He showed that the way to achieve peace and prosperity is to set individuals free. He attacked one type of government intervention after another. He recommended liberating Britain's American colonies. He denounced slavery. Smith had an enormous impact on ideas, where change begins.

Adam Smith Needs a Paper Clip: The pin factory, re-examined, by

Virginia Postrel,

Reason, May 2017

A short history of pins as fasteners from Adam Smith in the late 18th century to the invention of the paper clip at the turn of the 19th century

Adam Smith famously used a pin factory to illustrate the advantages of specialization, choosing this "very trifling manufacture" because the different tasks were performed under one roof ... By improving workers' skills and encouraging purpose-built machinery, the division of labor leads to miraculous productivity gains. Even a small and ill-equipped manufacturer, Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, could boost each worker's output from a handful of pins a day to nearly 5,000 ... In Smith's time and for a century after, pins were a multipurpose fastening technology.

The Ambitious, Accommodative Adam Smith [PDF], by Salim Rashid,

The Independent Review, 1997

Criticizes Adam Smith mostly based on his purported behavior, as evidenced in some of his personal writings and reports of some of his biographers, with minimal discussion of his economics or philosophical writings

The approach adopted in The Wealth of Nations attracts many readers because of its close link with natural-rights arguments and political radicalism. ... Many have noted Smith's sympathy for laborers and farm workers and his hostility toward masters and landlords. Combined with the general emphasis on liberty—recall the radical stress on liberty of his old teacher, Francis Hutcheson—the ideas would appear to have been a powerful solvent of traditional ideas, especially in Europe ...

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Who First Put Laissez-Faire Principles into Action, by

Jim Powell,

The Freeman, Aug 1997

Biographical essay, covering his life, works and involvement with the Physiocrats, as well as his accomplishments as an administrator

Referring to Turgot, Adam Smith wrote that "I had the happiness of his acquaintance, and, I flattered myself, even of his friendship and esteem." ... Turgot was in touch with others who embraced ideas of liberty. He dined with the Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith when he visited Paris in 1765, and later Turgot helped supply Smith with books for his work on The Wealth of Nations. But as intellectual historian Peter Groenewegen has shown, Turgot had little impact on Smith's writing, since Smith had already formed his principal views ... [B]oth men believed in economic liberty ...

Related Topics:

John Adams,

Bureaucracy,

Economic Barriers,

France,

Gold Standard,

Government,

Money,

François Quesnay,

Religious liberty,

Joseph Schumpeter,

Slavery,

Freedom of Speech,

Taxation,

Alexis de Tocqueville,

Trade,

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

Areopagitica: Milton's Influence on Classical and Modern Political and Economic Thought, by Isaac M. Morehouse, 15 Dec 2009

Discusses the four sections of Milton's 1644 pamphlet, the reasons for which and the environment in which it was published, and various lessons or parallels that can be made from an economic and political philosophy perspective

In his defense of free speech on moral grounds, we see in Milton much that would later be picked up by Adam Smith, both in his Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations. Of note is the notion that human vice cannot be done away with by imperial edict, but that a system must be allowed which manages, reduces, and channels vice to the best ends. For both Milton and Smith, that system required freedom from government interference. In one of Smith's most famous passages he says that under free-market competition, each person in their self-interest is guided, "as if by an invisible hand" to do good for society.

Barack Obama: The Anti Economic Growth President, by

Jim Powell, 29 Feb 2012

Lists and criticizes several of Obama's policies and proposals and discusses why economic growth and progress is beneficial

A key breakthrough in economic understanding came when the shy Scotsman Adam Smith wrote An Inquiry Into The Nature And Causes Of The Wealth Of Nations (1776). ... Smith's most famous lines: '[a typical investor] intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.'

Cantillon for Laymen, by Karen De Coster,

Mises Daily, 7 Jun 2006

Discusses in general terms the themes in Richard Cantillon's

Essai sur la nature du commerce en général (1755), including a short biographical section

This ... and has led many scholars, to label [Cantillon] — not Adam Smith — the father of modern economics (Thornton 1999, pp. 13-15) ... Cantillon's groundbreaking tract was of great importance for several reasons, the central reason being that he explained the economy as dynamic and unified, wherein entrepreneurs made profit in the pursuit of self-interest, what Adam Smith later termed "the invisible hand." ... One notable aspect of Cantillon's work is that he is quoted in Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, and citing others is something that Smith rarely did (Thornton 2001, p. 14).

Classical Liberalism in Argentina: A Lesson for the World, by

Jacob G. Hornberger,

Freedom Daily, Jul 1994

Highlights Argentine history from the 1810 revolution to the late 20th century, arguing that the period from 1852 to 1930 demonstrated the validity of Adam Smith's writings, also discussing 1958 visits by Leonard Read and Ludwig von Mises

Two centuries ago, Adam Smith asked a very fundamental question: what are the nature and causes of the wealth of nations? Note that Smith did not ask what most people today ask—that is, what are the causes of poverty? Smith understood that poverty had always been the natural state of mankind. He wanted to know something much more vital—what is it that causes certain nations to be wealthy and prosperous? ... Smith concluded that throughout history, it had been governments' attempts to defeat poverty that had prevented nations from becoming wealthy and prosperous.

David Hume and the Theory of Money, by

Murray N. Rothbard,

Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, 1995

Excerpted from section 15.4; brief overview and criticism of Hume's philosophical views followed by discussion of his monetary theory contrasting it with the thoughts of Cantillon, Turgot and Austrian school economists

David Hume (1711–76), the famous Scottish philosopher, was a close friend of Adam Smith's who was named Smith's executor ... Turning to the other areas of economics, it is possible that some of the deep flaws in Adam Smith's value theory were the result of David Hume's influence. For Hume had no systematic theory of value, and had no idea whatever of utility as a determinant of value. If anything, he kept stressing that labor was the source of all value.

Economic Ideas: Francis Hutcheson and a System of Natural Liberty, by

Richard M. Ebeling,

William Holden, 21 Nov 2016

Discusses the main themes in Hutcheson's

System of Moral Philosophy

Adam Smith was one of Hutcheson’s students in Glasgow, and his influence on Adam Smith was singularly significant, from everything from the importance of division of labor and the role of private property, to the normative notion of a free society based on a "system of natural liberty." ... this was, in essence, a central message in Francis Hutcheson's own political and economic philosophy. And it was the starting point for Adam Smith's own profound contributions a few decades later, after his time studying with Hutcheson at the University of Glasgow.

Francis Hutcheson: teacher of Adam Smith, by

Murray N. Rothbard,

Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, 1995

Section 15.2: discusses Hutcheson's life, the main economic themes in his writings and his criticism of Mandeville

The 'never-to-be-forgotten Dr. Hutcheson,' as Adam Smith referred to him in a letter half a century later, was the first Glasgow professor to teach in English instead of Latin ... His lectures ... drew students from all over Britain, the most famous of whom was Adam Smith, who studied under him from 1737 to 1740 ... The specific influences of Hutcheson on Adam Smith will be detailed further below; suffice it to say here that the order of topics of Hutcheson's lectures ... as heard by young Smith at the University of Glasgow, is almost the same as the order of chapters in the Wealth of Nations.

Frank A. Fetter: A Forgotten Giant, by Jeffrey Herbener, 16 Aug 2000

Biographical and bibliographical essay

Fetter also recognized the larger significance of a subjective value theory replacing an objective one in the history of economic thought. He said that, "the labor theory of value had been adopted by Adam Smith after only the most superficial discussion" which led him to "his confusion of ideas regarding labor embodied and labor commanded, labor as the source and as the measure of value, rent and profits now forming a part and now not a part of price." Fetter concluded, that "the resulting confusion was felt by all of the next generation of economists."

Frederic Bastiat, Ingenious Champion for Liberty and Peace, by

Jim Powell,

The Freeman, Jun 1997

Biographical essay of Frédéric Bastiat, covering those who influenced him as well as those influenced by him, his writings (including correspondence with his friend Coudroy), his roles in the French Constituent and Legistative Assemblies and his legacy

[Jean Baptiste Say] worked for a while in Britain before joining a Paris insurance company. There his boss suggested that he read Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations. The book thrilled him, and he resolved to learn more about how an economy works ... Say discarded Smith's labor theory of value, insisting that value was determined by customers.

Related Topics:

Frédéric Bastiat,

Richard Cobden,

Foundation for Economic Education,

Benjamin Franklin,

Government,

Henry Hazlitt,

Law,

The Law,

Libertarianism,

Liberty,

Gustave de Molinari,

Rights,

Jean-Baptiste Say,

Socialism,

The State,

Trade

Free Trade, by

Alan S. Blinder,

The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, 2008

Presents the case for free trade by pointing out various protectionist arguments which are mistaken or fall short of their presumed benefits

We understand intuitively that cutting ourselves off from specialists can only lower our standard of living. Adam Smith's insight was that precisely the same logic applies to nations. Here is how he put it in 1776:

It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy ... If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.

Full Context, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Freeman, Apr 2006

Explains why, when arguing against government interventions, such as an oil windfall-profits tax or labor market regulations, it is essential to be aware that the existing corporatist economy does not equate to the free market

In The Wealth of Nations Adam Smith famously wrote, "People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the publick, or in some contrivance to raise prices." It may seem strange that history's best-known advocate of the free market would cast such aspersions ... Opponents of the free market love that quote [but] they rarely add the sentences that follow: "It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice ..."

Hayek and the Scots on Liberty [PDF], by Gerald P. O'Driscoll, Jr.,

The Journal of Private Enterprise, 2015

Explores the influence of the eighteenth-century Scottish moral philosophers, mainly David Hume and Adam Smith, on Hayek's thinking about liberty and concepts such as natural law theory

Why did Hayek not rely more on Adam Smith? Hayek (1976a) provided an answer in a short essay, 'Adam Smith's Message in Today's Language.' He tells us that in forty years of lecturing, he always found the lectures on Smith 'particularly difficult to give.' ... Ebenstein ... tells us that Hayek's 'appreciation for Smith rose over his lifetime.' ... That assessment is supported by Hayek's characterization of Smith's contribution to the emergence of liberalism in the essay of that name. 'Adam Smith's decisive contribution was the account of a self-generating order which formed itself spontaneously if the individuals were restrained by appropriate rules of law'.

Home Study Course: Module 4: Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (Part I)

Fourth module of the Cato Home Study Course, includes link to listen or download audio program (2:33:34), questions and suggested readings

Adam Smith (1723-90) was not the first to try to understand the market economy, but he may have been the most influential and eloquent observer of economic life. His observation that a person may be "led by an invisible hand to promote an end that was no part of his intention" became the guiding star of an investigation of the beneficial unintended consequences of voluntary exchange, an investigation that still continues strong after more than two hundred years.

The Inherently Humble Libertarian, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 13 Feb 2015

Defends libertarianism from those who charge its advocates of "know-it-allness"

That ... is an allusion to Adam Smith's insight about the "man of system" in

The Theory of Moral Sentiments:

The man of system ... is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests, or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it. He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board ...

The Invisible Hand Is a Gentle Hand, by

Sharon Harris, 14 Sep 1998

Originally published at HarryBrowne.org; defends the free market and individual liberty, quoting among others Bastiat, Thomas Jefferson, David and Milton Friedman, John Lott, Isabel Paterson, Proudhon, Adam Smith, Sowell, John Stossel and Walter Williams

It's time to speak out for the free market and individual liberty. The great economist Adam Smith wrote that a free society operates as if "an invisible hand" directs people's actions—in such a way as to serve the interest of the whole society. That invisible hand is a gentle one ... The gentle invisible hand vs. the visible fist of government. Adam Smith said It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard for their own interest." In the marketplace, people tend to be well mannered—even if they hate you.

Related Topics:

Right to Keep and Bear Arms,

War on Drugs,

Eminent Domain Protections,

David D. Friedman,

Government,

Health care,

Market economy,

Medicine,

Private Property,

Prohibition,

Social Security Tax,

Society,

Lysander Spooner,

War

Jean-Baptiste Say: Neglected Champion of Laissez-Faire, by Larry J. Sechrest, 15 Jul 2000

Biographical and bibliographical essay, discussing Say's life, methodology and his writings on money, banking, the law of markets, entrepreneurship, capital, interest, value, utility, taxes and the state

Say did explicitly represent his work as being mainly an elaboration and popularization of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations for the benefit of continental European readers ... [A]lthough Say frequently praises Smith, he also departs from Smithian doctrine on a number of important points. In fact, Say even sharply criticizes Adam Smith on more than one occasion ... [T]hese two men represent two meandering, but generally divergent, paths embedded within classical economics. Smith leads one to David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall, Irving Fisher, John Maynard Keynes, and Milton Friedman.

Letters to Mr. Malthus, on Several Subjects of Political Economy, and on the Cause of the Stagnation of Commerce, by

Jean-Baptiste Say, 1820

Original title: Lettres à M. Malthus, sur différens sujets d'économie politique, notamment sur les causes de la stagnation générale du commerce

Series of five letters from Say to Malthus, written in response to the latter's criticisms in

Principles of Political Economy (1820); the letters were translated from the French by John Richter

Instead of weakening the authority of the celebrated Inquiry into the Wealth of Nations, I support it in the most essential part; but ... I think Adam Smith has forgotten some real exchangeable values, in omitting those which are attached to such productive services as leave no trace because they are totally consumed ... I revere Adam Smith—he is my master. When I took the first steps in political economy ... I stumbled at every move—he shewed me the true path. Supported by his Wealth of Nations, which shews at the same time his own intellectual wealth, I learned to go alone.

Related Topics:

Capital Goods,

Capitalism,

Economics,

Entrepreneurship,

Europe,

Farming,

Government,

Labor,

Prices,

Taxation,

Technology,

Trade,

United States

Liberalism, by

F. A. Hayek,

New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas, 1978

Chapter 9; originally written in 1973 and also published in Italian in

Enciclopedia del Novecento (1978); covers both the history of both strands of liberalism as well as a systematic description of the "classical" or "evolutionary" type

Adam Smith's decisive contribution [to the limited government doctrine] was the account of a self-generating order which formed itself spontaneously if the individuals were restrained by appropriate rules of law. His Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations marks perhaps more than any other single work the beginning of the development of modern liberalism. It made people understand that those restrictions on the powers of government which had originated from sheer distrust of all arbitrary power had become the chief cause of Britain's economic prosperity.

Libertarianism Is Not Atheist, Is Not Religious, by

Wendy McElroy,

The Daily Bell, 9 Oct 2014

Examines Rothbard's views in a 1987 article about freedom and religion, in particular regarding Ayn Rand's atheistic influences on early modern libertarianism

Adam Smith formulated well the distinction between political duty and morality. Each person had a political duty to not aggress against anyone else. For restraining his actions, however, no person deserved praise. He was simply performing his duty. Morality lay in the benevolent actions taken over and above the call of duty–in acts of kindness or charity, in comforting the afflicted or providing compassion. For such acts, a person deserved praise for being a moral human being.

Libertarianism: The Moral and the Practical, by

Sheldon Richman,

Future of Freedom, May 2014

Explores whether libertarian policies should distinguish between moral and practical concerns; revised version of "The Goal Is Freedom" column of 27 Dec 2013

I'm hardly alone in my uneasiness with this separation of concerns into the moral and the practical. In my camp is no less a personage than Adam Smith. Look at this passage from

The Wealth of Nations:

[The] happiness and perfection of a man, considered not only as an individual, but as the member of a family, of a state, and of the great society of mankind, was the object which the ancient moral philosophy proposed to investigate ...

... Smith's reference to "ancient philosophy" is a reference to Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle (and perhaps the Thomists whom they inspired) ...

Module 5: Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (Part II)

Fifth module of the Cato Home Study Course, includes link to listen or download audio program (2:34:19), questions and suggested readings

Adam Smith was both moral philosopher and social scientist. He sought to understand the wellsprings of morality as well as the regulating principles of social life. In seeking to understand the natural laws governing the regularities of economic life, Smith took the time to observe carefully how business enterprises operated, how markets were organized, and how the prices at which goods were exchanged were determined. Working out the relationships of "supply and demand" that determine prices in the market was one of his principal concerns.

Monetary Central Planning and the State, Part 30: The Gold Standard as Government-Managed Money, by

Richard M. Ebeling,

Freedom Daily, Jun 1999

Describes how, by allowing central banks to manage gold-backed currencies, the road was paved for central planning in other areas

In the 19th century there was ... a general agreement [among those who constructed and implemented government economic policies] with Adam Smith's observation that "the statesman, who should attempt to direct private people in what manner they ought to employ their capitals, would not only load himself with a most unnecessary attention, but assume an authority which could safely be trusted, not only to no single person, but to no council or senate, and which would nowhere be so dangerous as in the hands of a man who had the folly and presumption enough to fancy himself fit to exercise it."

Monopoly and Aggression, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 19 Dec 2014

Argues that monopoly and aggression are intimately related and that intellectual property laws are currently the main monopolistic interventions

Adam Smith's approach to monopoly makes more sense than the mainstream neoclassical view. To Smith, monopoly denoted a privilege, a legal barrier to competition, such as a license or a franchise—in other words, a grant from the state. Anyone who attempted to compete with the monopolist would run afoul of the law and be suppressed by force, because that's how the state assures its decrees are faithfully carried out. When someone whose actions are consonant with natural rights is suppressed by force, that is aggression.

Monopoly, Competition, and Educational Freedom, by

Jacob G. Hornberger, Mar 2000

Discusses monopolies and competition in the religious, postal delivery and educational realms and criticizes a speech by Gary Becker about competition in religion and education

Monopolies characterized the Age of Mercantilism in the 18th century. Over time, consumers came to hate monopolies, because monopolists, knowing that there was no threat of competition, were customarily arrogant and, more often than not, provided a shoddy product. With the publication of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations in 1776, people began seriously considering an alternative—the free market. Smith planted the seed that ultimately erupted into the Industrial Revolution. Monopoly privileges were repealed, and people were free to compete in the supplying of goods and services.

Murray Rothbard Confronts Adam Smith, by Paul B. Trescott,

The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 1998

Critical review of Rothbard's chapter about Adam Smith in

Economic Thought Before Adam Smith: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Volume I, including both positive and unfavorable points missed by Rothbard

Rothbard cites Schumpeter as one of the first to mount an authoritative deflation of Smith's exaggerated reputation. But Schumpeter also said that The Wealth of Nations "is a great performance all the same and fully deserved its success" ... Rothbard's treatment of Smith's is unfair and inaccurate. His treatment of Cantillon is distorted in the opposite direction. Ironically, many of Rothbard's specific criticisms of Smith would also apply to Cantillon and Turgot.

Murray Rothbard's Adam Smith, by Spencer J. Pack,

The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 1998

Supportive review of Rothbard's criticisms of Adam Smith in

An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought

Again, largely following Hume, Smith basically did not utilize a natural-law or natural-rights framework. His book on The Theory of Moral Sentiments was an elaborate argument for why humans can get along in society and why they do indeed have morals, wrapped around his theory of 'sympathy.' Although a case can be made that Smith's theory of justice was partly grounded in a natural-law position ... Smith for the most part never used natural-rights and natural-law theory.

National Servitude, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 21 Jun 2013

Discusses calls for "national service", contrasts them to insights from Frédéric Bastiat and Adam Smith, and counters possible objections

Adam Smith had more than a few insights into the services that human beings render one another ... [H]e wrote,

In civilized society [the individual] stands at all times in need of the co-operation and assistance of great multitudes, while his whole life is scarce sufficient to gain the friendship of a few persons ... [M]an has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only ...

Smith added later that a person's direct efforts to advance the social good are often less effective than efforts motivated by personal gain ...

Non-Marxist Theories of Imperialism, by Alan Fairgate,

Reason, Feb 1976

Examines writings of critics of imperialism that are not based on Marxist analysis

While early critiques of England's colonial foreign policy had focused primarily on political and moral objections, Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations presented the first comprehensive economic refutation of the mercantilist doctrines which had been used to justify the acquisition of colonies. Upholding the virtues of division of labor, economic specialization, and freedom of trade, Smith persuasively argued that protectionism and regulation of commerce would hamper, rather than promote, economic growth and welfare.

Related Topics:

Latin America,

Banking,

John Bright,

Richard Cobden,

John T. Flynn,

Foreign entanglements,

Garet Garrett,

Imperialism,

Leonard Liggio,

Militarism,

George Orwell,

Murray N. Rothbard,

Jean-Baptiste Say,

Joseph Schumpeter,

Joseph R. Stromberg,

William Graham Sumner

The Origin of Economic Theory: A Portrait of Richard Cantillon (1680-1734), by

Mark Thornton, 3 Aug 2007

Examines the sections of Cantillon's

Essai relating them to episodes in the author's life, then delving into several Austrian economics insights that can be found in the work

The Essai is considered influential for the development of both the Physiocrats and the classical economists, and Cantillon was one of the very few people mentioned by Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations. Unfortunately, Smith misrepresented Cantillon's work. Both Cantillon and his Essai were largely forgotten during the period of classical economics ... Most importantly, the Scottish philosopher and tax collector Adam Smith should no longer be considered the father of economics. That title now belongs to the Irish entrepreneur and Austrian economist, Richard Cantillon.

Peace and Pacifism, by

Robert Higgs,

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, 15 Aug 2008

Reviews what prominent classical liberals and libertarians had to say on the subject of peace and war, as well as the history of United States wars from the War of 1812 to the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the efforts of those who opposed them

Preeminent classical liberals, such as Adam Smith, Richard Cobden, John Bright, William Graham Sumner, and Ludwig von Mises, condemned war as fatal to economic and social progress. Smith famously taught that "little else is requisite to carry a [society] to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice: all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things."

Related Topics:

War,

American War Between the States,

Libertarianism,

Ludwig von Mises,

Murray N. Rothbard,

Freedom of Speech,

Lysander Spooner,

William Graham Sumner,

Vietnam War,

World War I,

World War II

Physiocracy, by

George H. Smith,

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, 15 Aug 2008

Discusses the Physiocrats, focusing mostly on Quesnay and his

Tableau Économique

Adam Smith writes in the Wealth of Nations that the physiocratic notion of a "barren or unproductive class" was an attempt to "degrade" merchants, manufacturers, and other nonagricultural workers with a "humiliating appellation." Some commentators disagree with Smith's assessment. They maintain that Quesnay and his disciples worked from a purely physical conception of productivity, and that in using the word sterile they did not mean to deny that members of this class provided goods and services that possessed economic utility.

The Physiocrats, by

Wendy McElroy,

Freedom Daily, Dec 2010

Discusses the 18th century French economists and their influences on Adam Smith, on American agriarianism and on Henry George

In the mid 1760s, professor of moral philosophy Adam Smith toured Europe at the behest of the wealthy Duke of Buccleuch who greatly admired Smith's recently published Theory of Moral Sentiments. It was during that period that Smith met Quesnay and commenced writing The Wealth of Nations ... In ... "Of Systems of Political Economy"—Smith details his several disagreements with the Physiocrats and then concludes that "with all its imperfections, [the Physiocratic system] is perhaps the nearest approximation to the truth that has yet been published upon the subject of political economy..."

Reasoning on the Nature of Things, by

Clarence B. Carson,

The Freeman, Feb 1982

Discusses how natural law doctrines were repudiated by utilitarians, why natural rights are important from an economic viewpoint, how the rights to life, liberty and property can be construed and what the author understands as the "social contract"

Smith maintained that the industrious individual in the pursuit of his own interest contributes to the well-being of others when he buys and sells goods in the market. He is bent to the pursuit of his own interest by nature, and his condition in this world is such that if he pursues it in a productive way he must contribute to the general stock of goods. In doing this, "he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases," Smith said, "led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was not part of his intention." There is a natural order of things ... which makes it so.

Related Topics:

Jeremy Bentham,

Government,

Law,

Liberty,

John Stuart Mill,

Philosophy,

Property Rights,

Ronald Reagan,

Rights,

Socialism,

Society

Self-Interest and Social Order in Classical Liberalism: Bernard Mandeville v. Francis Hutcheson, by

George H. Smith, 23 Jan 2015

Discusses the views of Hobbes and Mandeville regarding society and the need for government and the critiques of the latter made by Hutcheson and Adam Smith

Adam Smith later expressed similar objections in The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Mandeville's approach is 'wholly pernicious' because it 'seems to take away altogether the distinction between vice and virtue.' ... Moreover, contrary to Mandeville, Smith maintained that 'the desire of doing what is honourable and noble, of rendering ourselves the proper objects of esteem and approbation, cannot with any propriety be called vanity. Even the love of well-grounded fame and reputation, the desire of acquiring esteem by what is really estimable, does not deserve that name.'

The Spanish-American War: The Leap into Overseas Empire: Part 2, by

Joseph R. Stromberg,

Freedom Daily, Jan 1999

Discusses the Philippine-American War, that followed the Spanish-American War, and the actions and writings of the Anti-Imperialist League, William Graham Sumner and other opposed to the war and colonialism

[A]s Adam Smith wrote (oddly enough in 1776):

To found a great empire for the sole purpose of raising up a people of customers, may at first sight appear a project fit only for a nation of shopkeepers. It is, however, a project altogether unfit for a nation of shopkeepers; but extremely fit for a nation whose government is influenced by shopkeepers. Such statesmen, and such statesmen only, are capable of fancying that they will find some advantage in employing the blood and treasure of their fellow citizens, to found and maintain such an empire.

Student at Glasgow College, by John Rae,

Life of Adam Smith, 1895

Chapter II of

Life of Adam Smith, covering the years 1737 to 1740, and delving mostly on Smith's Moral Philosophy professor, Francis Hutcheson

... Smith improved his Greek under Dunlop, and acquired a distinct ardour for mathematics under the inspiring instructions of Simson ... He is sometimes considered a disciple of Hume and sometimes ... of Quesnay; if he was any man's disciple, he was Hutcheson's. ... His doctrine was essentially the doctrine of industrial liberty with which Smith's name is identified, and in view of the claims set up on behalf of the French Physiocrats that Smith learnt that doctrine in their school, it is right to remember that he was brought into contact with it in Hutcheson's class-room at Glasgow some twenty years before any of the Physiocrats had written a line on the subject ...

Tackling Straw Men Is Easier than Critiquing Libertarianism, by

Sheldon Richman, 5 Dec 2014

Counters John Edward Terrell's critique of libertarianism (in "Evolution and the American Myth of the Individual") using quotes from Adam Smith, Vernon Smith and Herbert Spencer

Has Terrell never heard of [Adam] Smith's The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1859—17 years before The Wealth of Nations and revised throughout his life? Or is he in that group of scribblers who think The Wealth of Nations was all that Smith had to say about the human enterprise? ... For Terrell's edification, I'll point out that The Theory of Moral Sentiments is an extended discussion of "fellow-feeling," that is, our natural sympathy for others. Smith would laugh at any portrayal of the isolated, allegedly self-sufficient individual as the summit of human development.

Why Those Who Value Liberty Should Rejoice: Elinor Ostrom's Nobel Prize, by

Peter J. Boettke,

The Freeman, Dec 2009

Discusses Elinor Ostrom's work and viewpoints, shortly after her being awarded the Nobel Prize in economics

In the history of political and economic thought the source of social order has been attributed either to the invisible hand of market coordination (Adam Smith) or the heavy hand of state control (Hobbes). Perhaps one of the best ways to understand Elinor Ostrom's work is to see it as working out a Hobbesian problem by way of a Smithian solution. That is perhaps a bit of a stretch but not by much.

Work!, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 7 Mar 2014

Contrasts the "gospel of work" and "joy of labor" espoused by moralists and state socialists with the views of economists such as Adam Smith, Bastiat, John Stuart Mill, Mises and Rothbard

Adam Smith and other early economists equated work with "toil," which is not a word overflowing with positive connotations. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith writes, "The real price of every thing, what every thing really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it. What every thing is really worth to the man ... is the toil and trouble which it can save to himself, and which it can impose upon other people. What is bought with money or with goods is purchased by labour, as much as what we acquire by the toil of our own body. That money, or those goods, indeed, save us this toil."

The Writings of Adam Smith, by Julio H. Cole,

The Freeman, Feb 1990

Biographical essay, including not only the two major works published during Adam Smith's lifetime, but also the lectures and other writing published posthumously

Smith took economics forever beyond the narrow mercantilistic framework which denied the gains from trade between nations, and made of it a study of the spontaneous and largely unintended social order which arises from free exchanges between individuals, exchanges which produce benefits for all parties involved, whether domestic or foreign. For as long as the love of liberty survives in this world, free men will continue to derive inspiration from Adam Smith, author of The Wealth of Nations.