Reference

John Stuart Mill, by Christopher Macleod,

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 25 Aug 2016

Major sections: Life - Mill's Naturalism - Mill's Theoretical Philosophy - Mill's Practical Philosophy - Bibliography

John Stuart Mill (1806–73) was the most influential English language philosopher of the nineteenth century. He was a naturalist, a utilitarian, and a liberal, whose work explores the consequences of a thoroughgoing empiricist outlook. In doing so, he sought to combine the best of eighteenth-century Enlightenment thinking with newly emerging currents of nineteenth-century Romantic and historical philosophy.

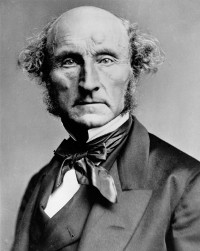

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873),

The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

Includes picture and list of selected works with links to those hosted by the Library of Economics and Liberty

The eldest son of economist James Mill, John Stuart Mill was educated according to the rigorous expectations of his Benthamite father. He was taught Greek at age three and Latin at age eight. ... After recovering from a nervous breakdown, he departed from his Benthamite teachings to shape his own view of political economy. In Principles of Political Economy, which became the leading economics textbook for forty years after it was written, Mill elaborated on the ideas of David Ricardo and Adam Smith.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), by Colin Heydt,

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Partial contents: Biography - Works: A System of Logic - Sir William Hamilton's Philosophy - Utilitarianism - On Liberty - The Subjection of Women and Other Social and Political Writings - Principles of Political Economy - Essays on Religion

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) profoundly influenced the shape of nineteenth century British thought and political discourse. His substantial corpus of works includes texts in logic, epistemology, economics, social and political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, religion, and current affairs. Among his most well-known and significant are A System of Logic, Principles of Political Economy, On Liberty, Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, Three Essays on Religion, and his Autobiography.

Mill, John Stuart (1806-1873), by

Aeon Skoble,

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, 15 Aug 2008

Biographical essay

John Stuart Mill was educated by his father James Mill and received training in a variety of disciplines, including classics, philosophy, history, economics, mathematics, and logic ... He was able to read Greek at age 3 and Latin at age 8. For 35 years, he worked for the East India Company, but managed to write on a variety of topics ... Mill is remembered primarily for his contributions to moral and political philosophy and logic. In later years, Mill developed strong sympathies for certain sorts of government intervention, both in the economy and socially, but for a good portion of his life he can reasonably be described as a libertarian.

Born

20 May

1806, John Stuart Mill, in Pentonville,

London

Biography

John Stuart Mill (1806 - 1873), by Thomas Mautner (editor),

The Penguin Dictionary of Philosophy

During his lifetime, it was his essay On Liberty 1859 that aroused the greatest controversy, and the most violent expressions of approval and disapproval. The essay was sparked by the feeling that Mill and his wife, Harriet Taylor, constantly expressed in their letters to one another: that they lived in a society where bold and adventurous individuals were becoming all too rare.

Web Pages

4 Things You Probably Never Knew About John Stuart Mill,

LearnLiberty.org, 20 May 2016

Brief introduction to Mill followed by four interesting facts about his life and thought

John Stuart Mill was born exactly 210 years ago (May 21, 1806), and he's still remembered as one of the most foundational classical liberal philosophers and political economists to this day ... [Y]ou probably remember him for his development of utilitarian thought—the idea that anything we do should bring about "the greatest happiness of the greatest number," and that good moral behavior is the best way to achieve happiness for as many people as possible. A moral system is only good, argued Mill, if it can accomplish this end.

John Stuart Mill - Libertarianism.org

Short profile and links to essays, columns and other resources about Mill

Raised since early childhood to promote Jeremy Bentham's theory of utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill both expanded on those ideas and developed many of his own regarding individual freedom and liberty. Inspired by his good friend and wife, Mill was one of the first men to publish a book explicitly on women's rights; he viewed the subjugation of women as one of the worst vestiges of ancient society. Mill is probably best known for his harm principle and the theory of tyranny of the majority.

John Stuart Mill - Online Library of Liberty

Includes portrait, short biography, links to essays about Mill, timeline of his life and works, to various versions of his works and to selected quotations

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was the precocious child of the Philosophical Radical and Benthamite James Mill. Taught Greek, Latin, and political economy at an early age, He spent his youth in the company of the Philosophic Radicals, Benthamites and utilitarians who gathered around his father James. J.S. Mill went on to become a journalist, Member of Parliament, and philosopher and is regarded as one of the most significant English classical liberals of the 19th century.

Articles

Herbert Spencer as an Anthropologist [PDF], by

Robert L. Carneiro,

The Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1981

Traces Spencer's contributions to the fields now known as anthropology and sociology and how his concept of cultural evolution was developed

John Stuart Mill, the leading English disciple of [Auguste] Comte, took up the argument for a social science in "The Logic of the Moral Sciences," Part 6 of his famous book, A System of Logic, concluding that human actions are subject to the laws of causality ... [I]n the 8th edition ... Mill wrote: "That the collective series of social phenomena, in other words, the course of history, is subject to general laws, ... has been familiar for generations to the scientific thinkers of the Continent. ... In our own country, however, at the time of first publication [1843], it was almost a novelty."

John Stuart Mill and the Three Dangers to Liberty, by

Richard M. Ebeling,

Freedom Daily, Jun 2001

Evaluates John Stuart Mills arguments in his essay "On Liberty", in particular the three forms of tyranny posited by Mill and his lack of emphasis on private property and the "voluntary relationships of the market economy"

John Stuart Mill's 1859 Essay "On Liberty” is one of the most enduring and powerful defenses of individual freedom ever penned ... Mill not only defended freedom of thought but liberty of action as well ... [T]he weakest point in Mill's defense of individual liberty is his failure to clearly align his case for human freedom with the right to private property and its use in all ways that do not violate the comparable individual rights of others. But within the context of his own premises, Mill was a fairly strong advocate of much of what today we usually call civil liberties.

John Stuart Mill - Hero of the Day,

The Daily Objectivist, 2000

Biographical profile published by

The Daily Objectivist; includes excerpts from Mill's

Autobiography (1873)

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), author of On Liberty and Principles of Political Economy, received quite a strenuous education from his father, James, whose Benthamite utilitarianism he adopted as his own. In addition to his economic and political thinking, Mill is credited with formulating (in his System of Logic [1848]) five guiding principles of induction—the method of agreement, the method of difference, the joint method of agreement and difference, the method of residues, and the method of concomitant variations.

Libertarianism and Legal Paternalism [PDF], by

John Hospers,

The Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1980

Discusses laws "designed to protect people from themselves" arguing that in general such laws are illegitimate

"Neither one person, nor any number of persons," wrote John Stuart Mill in On Liberty, "is warranted in saying to another human creature of ripe years, that he shall not do with his life for his own benefit what he chooses to do with it. ... The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinion of others, to do so would be wise, or even right."

Module 8: John Stuart Mill's On Liberty and Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Eighth module of the Cato Home Study Course, includes link to listen or download audio program (two parts, 1:15:47 and 1:25:24), questions and suggested readings

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), one of the best known intellectual figures of the nineteenth century, is especially revered by civil libertarians ... for his essay On Liberty, published in 1859. Mill's principal concern was to ensure that individual liberty was not swallowed up in the move toward popular sovereignty ... Mill's account of the need to protect individual liberty from "the tyranny of the majority" has been highy influential–notably his defense of freedom of speech as a process of determining the truth; being "protected" from falsehood is the same as being "protected" from the possibility of knowing truth.

Monetary Central Planning and the State, Part 29: The Gold Standard in the 19th Century, by

Richard M. Ebeling,

Freedom Daily, May 1999

Discusses the evolution of the gold standard, from the creation of the Bank of England (1694), the Bank Restriction Act (1797), arguments for its repeal by David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill, and its international development until the 1890s

John Stuart Mill, in his 1848

Principles of Political Economy, expressed the widely shared view that if no check was placed on the power of issuers of paper money,

the issuers may add to it indefinitely, lowering its value and raising prices in proportion; they may, in other words depreciate the currency without limit. Such a power, in whomsoever vested, is an intolerable evil ... The temptation to over-issue in certain financial emergencies is so strong, that nothing is admissible which can tend, in however slight a degree, to weaken the barriers that restrain it.

Monetary Central Planning and the State, Part XVIII: Say's Law of Markets and Keynesian Economics, by

Richard M. Ebeling,

Freedom Daily, Jun 1998

Contrasts the views of John Maynard Keynes with "the commonsense foundations of economics" by explaining the basics of exchange and markets, and discussing Say's Law and John Stuart Mill's refinement

The answer ... was already suggested ... by the English classical economist John Stuart Mill in a restatement and refinement of Say's law of markets. In an essay entitled "Of the Influence of Consumption on Production" (1844), Mill argued that as long as there are any ends or wants that men desire that have not as yet been satisfied, there is always more work to be done ... But Mill admits that there may be times when individuals, for various reasons, may choose to hoard, or leave unspent in their cash holding, a greater proportion of their money income than is the usual practice.

On Liberty & License, by H. Maitre,

Reason, Dec 1976

Discusses commentary by supposedly "conservative libertarians" on Nozick's

Anarchy, State, and Utopia and worries about "the amoralism of some of the libertarian movement"

In his essay On Liberty, John Stuart Mill thinks it established beyond question that parents have the duty to see that their children are properly schooled. He demands that ... the parents be fined if the child fails to meet certain standards ... Yet in the same essay Mill states that he cannot see any reason or justification for any given society to impose its own civilization on another society ... It must be expected that Nozick would strongly disagree with Mill's advocacy of compulsory proper schooling and that he would just as strongly agree with Mill's objection to intervention.

Real Liberalism and the Law of Nature, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 10 Aug 2007

Examines Thomas Hodgskin's introductory letter to Henry Brougham, a Member of Parliament (later Lord Chancellor), written in 1829, published in

The Natural and Artificial Right of Property Contrasted (1832)

Hodgskin goes on:

On the contrary, both Mr. [John Stuart] Mill and M. [Etienne] Dumont, describe the right of property to be the offspring of law. Mr. Mill says, "the end of government is to make a distribution of wealth," or create such a right ...

...

... Messrs. Bentham and Mill, both being eager to exercise the power of legislation, represent it as a beneficent deity which curbs our naturally evil passions and desires (they adopting the doctrine of the priests, that the desires and passions of man are naturally evil)—which checks ambition, sees justice done, and encourages virtue.

Reasoning on the Nature of Things, by

Clarence B. Carson,

The Freeman, Feb 1982

Discusses how natural law doctrines were repudiated by utilitarians, why natural rights are important from an economic viewpoint, how the rights to life, liberty and property can be construed and what the author understands as the "social contract"

John Stuart Mill attacked the very notion of a benevolent and orderly nature (attacking nature and charging it with cruelties much in the manner that some attack or question God). He said, "Nature impales men, breaks them as if on the wheel, casts them to be devoured by wild beasts, burns them to death, crushes them with stones ..., starves them with hunger, freezes them with cold, poisons them ..., and has hundreds of other hideous deaths in reserve ..." ... Mill was, of course, dealing with nature in the concrete, as many romantics did, but without their admiration of it.

Related Topics:

Jeremy Bentham,

Government,

Law,

Liberty,

Philosophy,

Property Rights,

Ronald Reagan,

Rights,

Adam Smith,

Socialism,

Society

The Sphere of Government: Nineteenth Century Theories: 1. John Stuart Mill, by

Henry Hazlitt,

The Freeman, Jan 1980

Critiques John Stuart Mill's ideas on what are the "necessary" and "optional" functions of government, as presented in his

Principles of Political Economy (1848)

Mill's main discussion of the problem [of government power] occurs in Volume II (Book V ...) of his Principles of Political Economy ... When one recalls that Mill was brought up in the laissez-faire tradition, some of his conclusions may seem surprising ... Mill ends by granting most of the contentions of the present-day statists. As he keeps adding to his list of "exceptions" to the general rule of laissez-faire, he gradually seems to forget all his earlier warnings against piling an unmanageable number of functions on the state and building excessive powers that can more easily be abused.

Szasz on the Liberal Tradition, by

David Gordon,

The Mises Review, Sep 2004

Review of Szasz' book

Faith in Freedom: Libertarian Principles and Psychiatric Practices, highlighting his criticisms of J.S. Mill, Mises, Hayek, Rothbard and Nozick

One might have guessed that Szasz would view John Stuart Mill with unstinting admiration. Not only did Mill defend individual autonomy; he specifically denounced in On Liberty the practice of stigmatizing eccentrics as madmen. Szasz ... cites instead a letter of 1858 in which Mill denounces the 'frightful facility' with which someone can be committed without trial for lunacy. Instead, Mill thought that no one should be committed without inquiry by jury, though he recognized that juries 'are only too willing to treat any conduct as madness which is ever so little out of the common way'

Vouchers and Educational Freedom: A Debate, by

Joseph L. Bast,

David Harmer,

Douglas D. Dewey,

David Boaz (introduction),

Policy Analysis, 12 Mar 1997

Debate between Joseph L. Bast, Heartland Institute president, and David Harmer, former Heritage Foundation researcher, versus Douglas Dewey, National Scholarship Center president

The authors are 100 percent committed to getting government out of the business of educating our children. We heartily concur with John Stuart Mill's observation:

A general state education is a mere contrivance for molding people to be exactly like one another; and as the mold in which it casts them is that which pleases the predominant power in the government ... it establishes a despotism over the mind, leading by natural tendency to one over the body.

Work!, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 7 Mar 2014

Contrasts the "gospel of work" and "joy of labor" espoused by moralists and state socialists with the views of economists such as Adam Smith, Bastiat, John Stuart Mill, Mises and Rothbard

We see this same lack of enthusiasm for work in John Stuart Mill, an influential classical economist as well as a philosopher ... Mill wrote an anonymous response [to Carlyle] in the following issue ... "While we talk only of work, and not of its object, we are far from the root of the matter ... In opposition to the 'gospel of work,' I would assert the gospel of leisure, and maintain that human beings cannot rise to the finer attributes of their nature compatibly with a life filled with labor ... the exhausting, stiffening, stupefying toil of many kinds of agricultural and manufacturing laborers ..."

Writings

Bentham,

London and Westminster Review, Aug 1838

Opens by contrasting Bentham as a Progressive and Coleridge as a Conservative, then proceeds to examine and criticize Bentham philosophical method, and then his theories of life, law, government and utility

He was a man both of remarkable endowments for philosophy, and of remarkable deficiencies for it; fitted, beyond almost any man, for drawing from his premises, conclusions not only correct, but sufficiently precise and specific to be practical; but whose general conception of human nature and life furnished him with an unusually slender stock of premises.

Book chapters

Liberalism, by

F. A. Hayek,

New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas, 1978

Chapter 9; originally written in 1973 and also published in Italian in

Enciclopedia del Novecento (1978); covers both the history of both strands of liberalism as well as a systematic description of the "classical" or "evolutionary" type

John Stuart Mill, in his celebrated book On Liberty (1859), directed his criticism chiefly against the tyranny of opinion rather than the actions of government, and by his advocacy of distributive justice and a general sympathetic attitude towards socialist aspirations in some of his other works, prepared the gradual transition of a large part of the liberal intellectuals to a moderate socialism. This tendency was noticeably strengthened by the influence of the philosopher T. H. Green ...

Book chapters

Introductory,

On Liberty, 1859

Chapter I; explains the subject of the essay, namely, "the nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual"

The subject of this Essay is not the so-called Liberty of the Will, so unfortunately opposed to the misnamed doctrine of Philosophical Necessity; but Civil, or Social Liberty: the nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual ...

[A] thorough consideration of this part of the question will be found the best introduction to the remainder. Those to whom nothing which I am about to say will be new, may therefore, I hope, excuse me, if on a subject which for now three centuries has been so often discussed, I venture on one discussion more.

Interviews

Interview with Adam Smith [via Edwin West], by

E. G. West,

The Region, Jun 1994

Professor Edwin G. West stands in for Adam Smith and answers questions from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis banking and policy issues magazine,

The Region

Smith: I believe that the main intellectual revolution you are speaking of was that pioneered by John Stuart Mill in his Principles of Political Economy ... The laws of production, Mill argued, have the properties of inexorable natural laws whereas the laws of distribution are subject to human invention and institutions. And if the laws of distribution are man-made then existing property relations can be interfered with on the principle of equity. It was in this way that Mill introduced the search for practical means of redistribution as a crucial part of the political economist's task.

Related Topics:

Banking,

Central Banking,

Economic Freedom,

Educational freedom,

Hong Kong,

India,

Japan,

Minimum Wage Laws,

Russia,

Adam Smith,

Taxation

Books Authored

Autobiography, 1873

Partial contents: I. Childhood and Early Education - II. Moral Influences in Early Youth. My Father's Character and Opinions - III. Last Stage of Education and First of Self-education - IV. Youthful Propagandism. The Westminster Review

On Liberty, 1859

Contents: I. Introductory - II. Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion - III. Of Individuality, as One of the Elements of Well-Being - IV. Of the Limits to the Authority of Society over the Individual - V. Applications

Principles of Political Economy, 1848

Contents: Introduction, by W. J. Ashley - Preface - Preliminary Remarks - I. Production - II. Distribution - III. Exchange - IV. Influence of the Progress of Society on Production and Distribution - V. On the Influence of Government

Videos

John Stuart Mill: A Biography, by Nicholas Capaldi,

Brian Lamb,

Booknotes, 1 Mar 2004

Lamb interviews Nicholas Capaldi, author of

John Stuart Mill: A Biography