Web Pages

Home Study Course: Module 3: Thomas Paine's Common Sense and Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence

Third module of the Cato Home Study Course, includes link to listen or download audio program (two parts, 1:18:20 and 1:13:52), questions and suggested readings

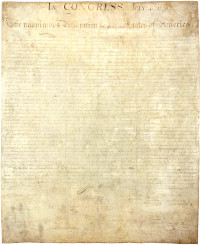

The Declaration ... is more than a mere declaration of intention to sever political ties with Britain. It is a carefully crafted argument justifying that ... It ranks as one of the ... most influential political documents of all time ... The Founders offered a careful set of arguments for armed revolution, a course that was not undertaken lightly, with full awareness of the consequences. When he signed a document that concluded, "We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor," each signatory knew that he was signing his own death warrant in the event of failure.

Articles

Autobiography, by

Thomas Jefferson, 29 Jul 1821

Covering the period from 1743 (his childhood, with background on his parents) to 1790 (shortly after his return from Paris and before assuming his office as U.S. Secretary of State); written during 6 Jan-29 July 1821

It appearing in the course of these debates that the colonies of N. York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and South Carolina were not yet matured for falling from the parent stem ... it was thought most prudent to wait a while for them ... but that this might occasion as little delay as possible a committee was appointed to prepare a declaration of independence. The commee were J. Adams, Dr. Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert R. Livingston & myself ... The committee ... desired me to do it. It was accordingly done, and being approved by them, I reported it to the house on Friday the 28th of June ...

Benjamin Franklin: The Man Who Invented the American Dream, by

Jim Powell,

The Freeman, Apr 1997

Lengthy biographical essay, including a section on the posthumous publication and reaction to Franklin's

Autobiography

On June 21, 1776, Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston (New York), and Roger Sherman (Connecticut) were appointed to a committee for producing a declaration which would announce American independence. The committee asked Jefferson to draft it ... Handwritten revisions suggest it was Franklin's idea to change Jefferson's description of "sacred and undeniable truths" to "self-evident." ... Franklin changed Jefferson's phrase "deluge us in blood" to "destroy us." And he had a number of other changes that tightened up Jefferson's magnificent draft.

Related Topics:

John Adams,

American Revolutionary War,

United States Constitution,

Entrepreneurship,

France,

Benjamin Franklin,

Thomas Jefferson,

Massachusetts,

Thomas Paine,

Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia,

No quartering of Soldiers,

Taxation,

George Washington

The Declaration of Independence in American, by

H. L. Mencken, 7 Nov 1921

Originally "Essay in American"; reprinted in

The American Language, third edition, 1923; includes a preface explaining why the original Declaration is "quite unintelligible" to the average current-day (1920's) American

All we got to say on this proposition is this: first, me and you is as good as anybody else, and maybe a damn sight better; second, nobody ain't got no right to take away none of our rights; third, every man has got a right to live, to come and go as he pleases, and to have a good time whichever way he likes, so long as he don't interfere with nobody else. That any government that don't give a man them rights ain't worth a damn; also, people ought to choose the kind of government they want themselves, and nobody else ought to have no say in the matter.

Do Our Rights Come from the Constitution?, by

Jacob G. Hornberger,

Freedom Daily, Jun 1999

Dispels the myth that rights are granted to the people by the Constitution or the Bill of Rights

[W]ith the publication of the Declaration of Independence, ... the historical concept of sovereignty got turned upside down ... The Declaration emphasizes that men have been endowed with certain fundamental and inherent rights that preexist government ... It also emphasizes that the reason people call government into existence is to protect the exercise of these rights ... The Declaration tells us that it is the right of the people to alter or abolish that government and to implement a new government that is designed to protect, not destroy, the exercise of man's natural or God-given rights.

Independence Day Address in Kansas City, MO, by

Andre Marrou, 4 Jul 1992

After quoting the "self-evident truths" paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, lists how the signers suffered, and contrasts them with government actions since 1913 that betrayed those ideals

The 56 men who signed the Declaration suffered greatly for their courageous act:

- 5 were captured by the British and tortured to death;

- 12 had their homes destroyed;

- 9 of them died in combat, and

- 3 of them lost their sons in the army.

All told, more than half of the signers endured terrible hardships. But their patriotism and devotion to liberty were not in vain. For 137 years, or until 1913, the country enjoyed life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness under a small, constitutional, benign government. Then things went awry. The ideals ... were to be betrayed repeatedly.

Independence Day Propaganda, by

Anthony Gregory,

LewRockwell.com, 4 Jul 2011

Argues that the American Revolution, albeit of a libertarian flavor, had several unsavory shortcomings both before and after 4 July 1776

Even the Declaration of Independence, whose adoption is celebrated on July Fourth, features unfortunate examples of hypocrisy. Consider the condemnation of the British for turning the "savage" American Indians against the colonists. There was some validity to the complaint, but coming from a political leadership that had allied with at least some "savages" not so long before in the war with France, and who soon enough instituted a nearly genocidal policy of expansionist displacement of the Indians, this is no minor defect in the Declaration's language.

Jefferson, Thomas (1743-1826), by Daniel J. Mahoney,

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, 15 Aug 2008

Biographical essay

In 1775–1776, Jefferson was a Virginia delegate to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where in June 1776 he drafted the Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Congress on July 4. As he later described his purpose, he sought 'to place before mankind the common sense of the subject'—justification of American independence—'in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent.' In doing so, he also defined the American philosophy of government, which was premised on the fact that each person, by virtue of his or her humanity alone, possessed inherent natural rights, among them the rights of 'life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.'

Keynote Address to the LP Convention, by

M. Rothbard,

The Libertarian Forum, Aug 1977

Speech at the National Convention in July 1977; based on the "Turning Point, 1777/1977" Libertarian Party convention theme, compares the American Revolution against the British with the contemporary libertarian situation versus the state

[A]s noble, as exciting, as profoundly libertarian as the Declaration was, it was still the necessary but not sufficient first step in the victory of what we have correctly identified as the First Libertarian Revolution. The Declaration was the rhetoric ... that set the stage; but the ... revolutionaries ... were not only interested in setting forth a glorious set of principles; ... they were also interested ... in putting these principles into practice ... It is only because of their dedicated actions that we, their descendants, can celebrate the 4th of July and the Declaration ...

Leonard E. Read: A Portrait, by

Edmund A. Opitz,

The Freeman, Sep 1998

Memorial and biographical essay, focusing mostly on Read's life before founding FEE; written for the centennial of his birth

The Declaration of Independence was Leonard’s favorite. Permit me to quote from Read's interpretation of a portion of one sentence. "... in the fraction of one sentence written into the Declaration of Independence," Read declared, "was stated the real American Revolution, the new idea, and it was this: 'that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights; that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.' That was it. This is the essence of Americanism. This is the rock upon which the whole 'American miracle' was founded ..."

Natural Law and the American Tradition, by Davis E. Keeler,

The Freeman, May 1981

Discusses the influence of Edward Coke and William Blackstone in early colonial America

The Declaration of Independence was a statement of these principles. Far from being an extravagant rallying cry for a difficult cause, it was a simple statement of the general political and legal consensus of the colonists. When the infuriated colonists denounced the Stamp Tax and demanded the rights of Englishmen, they were not demanding those rights which Parliament had from time to time granted its subjects but rather those immemorial rights of Englishmen granted by God and manifest in nature which no parliament however representative may take away or alter.

New Declaration of Independence, by

Vincent H. Miller,

Jarret B. Wollstein,

ISIL.org, Jan 2000

Prefaced by quoting the second paragraph of the original Declaration, lists—in a manner similar to the original—the outrages of the "modern American State" (referred to as "They") and ending with a list of demands

Two hundred years ago our ancestors signed a document which forever changed the course of history: the Declaration of Independence. That document ... established for the first time a society based on the principle of the rule of law and limited government ... But, bit by bit, the principles which made this country great have been forgotten–to the point where the uncontrolled growth of government now threatens to totally destroy our liberty and our prosperity. Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, and the other signers of the original Declaration of Independence were well aware of that danger.

The Roots of Modern Libertarian Ideas, by

Brian Doherty,

Cato Policy Report, Mar 2007

Survey of the history of libertarian ideas, from ancient China and Greece to 20th century writers; adapted from

Radicals for Capitalism (2007)

The libertarian vision is in the Declaration of Independence: we are all created equal; no one ought to have any special rights and privileges in his social relations with other people. We have certain rights—to our life, to our freedom, to do what we please in order to find happiness. Government has just one purpose: to help us protect those rights. And if it doesn't, then we get to "alter or abolish it." It's hard to imagine a more libertarian document, but there it is: a sacred founding document of the United States of America.

The Scoundrel Robert Morris, by

Douglas E. French,

The Free Market, Feb 1995

Examines claims made about financier Robert Morris by RMA, originally eponymously named after him

An RMA publication claims Robert Morris was an "American patriot who signed the Declaration of Independence and helped finance our Revolutionary War and establish our banking system." An "American patriot"? Hardly ... As a member of the Continental Congress, Morris voted against independence in July 1776. He was not a friend of freedom, but a pragmatic businessman, and did not want to disrupt his many English trading relationships. But changes in the political winds resulted in his signature on the Declaration of Independence the following month.

The Spirit of Humility [PDF], by

Stanley Kober,

Cato Journal, 1997

Discusses the recognition of the limits on human knowledge, which the author claims leads to the title spirit as evidenced in "the American experiment" and its possible lessons for European unification

For democratic government to endure, therefore, it must be based on a universal conception of human rights. This was the spirit of the American Declaration of Independence, as Lincoln observed in his response to the Supreme Court's decision in the Dred Scott case, in which the Court decided that slaves could not be considered equal to other human beings. Lincoln replied that the words of the Declaration could not be confined to the white inhabitants of the United States, but had a universal application.

The Third Amendment and the Issue of the Maintenance of Standing Armies: A Legal History, by

William S. Fields,

David T. Hardy,

American Journal of Legal History, 1991

Examines the history of quartering of soldiers in private residences and the maintenance of standing armies, both in England and the United States revolutionary and constitutional convention periods

In the Declaration, the complaint against the maintenance of a standing army was recognized as political in nature and was leveled against the king alone ...; while the grievance against the involuntary quartering of soldiers was viewed as a violation of the colonists rights as Englishmen and was attributed to both king and parliament ... However, the use of the term "large bodies of armed troops" instead of simply "soldiers," in its reference to the quartering problem, was indicative of the close relationship between the standing armies and quartering grievances.

Related Topics:

Standing Army,

United States Bill of Rights,

Edward Coke,

Thirteen Colonies,

England,

Patrick Henry,

James Madison,

George Mason,

New York City,

Petition of Right,

Philadelphia,

No quartering of Soldiers

The Third Amendment: Forgotten but Not Gone, by

Tom W. Bell,

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, Jul 1999

Intends to fill "the most glaring" gaps in previous Third Amendment scholarship, including its connection to the property rights covered by the Fifth Amendment

Parliament's response to the Boston Tea Party triggered a series of political statements that addressed the quartering issue, culminating in the Declaration of Independence ... The First Continental Congress complained of this latest Quartering Act in its Declaration and Resolves of 1774 ... In 1775, the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms also cited the 1774 statute passed "for quartering soldiers upon the colonists in time of profound peace." Finally, the Declaration of Independence justified breaking the "political bands" that had bound the colonists to England ...

Related Topics:

American Revolutionary War,

American War Between the States,

Eminent domain,

England,

France,

London,

James Madison,

Magna Carta,

New York,

Petition of Right,

No quartering of Soldiers

Thomas Jefferson's Sophisticated, Radical Vision of Liberty, by

Jim Powell,

The Freeman, Jul 1995

Biographical essay, highlighting Jefferson's "felicity of expression" that led him to write the famous words in the Declaration of Independence

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee urged the Continental Congress to adopt his resolution for independence. Debate was scheduled for July 1, while Jefferson, Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston were assigned to prepare a statement announcing and justifying independence. Thirty-three-year-old Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence on the second floor of a Philadelphia home belonging to bricklayer Jacob Graff, where he rented several rooms ... By habit, he did most of his writing between about 6:00 PM and midnight. The Declaration took him 17 days.

To Defeat the Assault on Liberty, Our Appeals Must Be Moral, by

Jim Powell, 13 May 2013

Argues, by providing several historical examples, that "compelling moral appeals for liberty" are needed to confront various current problems such as government spending and debt, higher taxes and disregard of constitutional limits on executive power

Thomas Jefferson made one of the most famous moral appeals in the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence ... The Declaration resonated with people around the world. The first of dozens of German translations appeared on July 9, 1776. French translations ... circulated throughout Europe, from Paris to Berlin and St. Petersburg. During the 19th century, it was translated into Chinese, Japanese, Polish, Russian, Spanish and other languages. Well into the 20th century, new nations issued declarations that adopted phrases from the American Declaration of Independence.

Was the Constitution Really Meant to Constrain the Government?, by

Sheldon Richman,

The Goal Is Freedom, 8 Aug 2008

Explains how attempting to revert to the "original meaning" of the Constitution or appealing to the writings of the framers is not a shortcut leading to a free society

We could answer that question by pointing to the Declaration of Independence, which embraces the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But does that really get us out of the woods? Someone who believes the Preamble authorizes the welfare state will similarly believe the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness entail the welfare state. But even if the Declaration resists that interpretation, we must note, as Jensen did, that the founding fathers who wrote the Constitution of 1787 were quite a different set of men from those who signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Why Should a Supreme Court Justice Care about Natural Rights?, by

Jim Powell, 9 Jul 2010

Discusses the evasiveness of Supreme Court nominee Elena Kagan when asked about the Declaration of Independence, and argues why justices should heed the natural rights philosophy embodied by its most famous lines

The immortal opening lines of the Declaration affirm that individuals have rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness because they're human beings, regardless what a law might say. This, the philosophy of natural rights, is crucial because throughout history laws have suppressed liberty. ... In August 1963, at the March on Washington, King appealed to the principles of the Declaration of Independence when he said: 'I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed —we hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.'

The Wisdom of LeFevre, by

Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr.,

The Free Market, Jul 2001

Discusses various aspects of Robert LeFevre's thoughts, e.g., the distinction between true and artificial government, patriotism, and includes excerpts from a draft new Declaration of Independence

It was the Declaration of Independence that firmly established the right of a people to resist and secede from state control. "So important is the right and duty of the people to dispense with despotism," [LeFevre] wrote, "this great Declaration contains the sentence not once, but twice. In its final utterance, ... it calls for 'new guards' which may or may not entail such a unit as an artificial agency." He further said that "the bill of grievances contained in the immortal Declaration of Independence could be extended by our own citizens in modern times, had they the stomach for it."

Book chapters

John Adams, by

John Fiske,

The Presidents of the United States, 1789-1914, 1914

Biographical essay; includes picture of Adams (painting by Gilbert Stuart), photograph of the Braintree houses where he was born; facsimile of a letter with his signature and a section on his wife Abigail

On June 7 the declaration of independence was moved by Richard Henry Lee, of Virginia, and seconded by John Adams. The motion was allowed to lie on the table for three weeks, in order to hear from the colonies of Connecticut, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and New York, which had not yet declared their position ... On July 1 Mr. Lee's motion was taken up by congress sitting as a committee of the whole; and, as Mr. Lee was absent, the task of defending it devolved upon Mr. Adams ... Adams's speech on that occasion was probably the finest he ever delivered.

Interviews

The Plowboy Interview: Karl Hess, by

Karl Hess,

Anson Mount (interviewer),

Mother Earth News, Jan 1976

Karl Hess interview in issue No. 37, Jan/Feb 1976, shortly after his book

Dear America (1975) had become a bestseller, questions him about the switch from right wing conservatism to the New Left

HESS: ... [T]he Internal Revenue Service took a dim view of [not paying taxes] and ... apparently decided that I'm a one-man movement to overthrow the government.

PLOWBOY: Are you?

HESS: As far as I'm concerned, the federal government is overthrown because the Declaration of Independence clearly states that when a government gets to be intolerable, concerned citizens should abolish it. So I wrote a letter to the government saying that it was abolished. Interestingly enough, however, the Declaration of Independence has no current legal standing. The Constitution superseded it unfortunately.