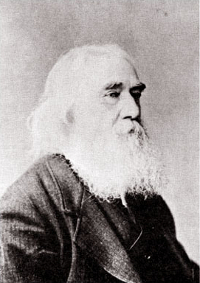

Lysander Spooner (1808-1887) was an American individualist anarchist. He was also an abolitionist, entrepreneur, essayist, legal theorist, pamphletist, political philosopher, Unitarian, writer and a member of the International Workingmen's Association (First International).

Spooner was a strong advocate of the labor movement and anti-authoritarian and individualist anarchist in his political views. His economic and political ideology has usually been identified as libertarian socialism, free-market socialism, and mutualism. His writings contributed to the development of both left-libertarian and right-libertarian political theory within libertarianism in the United States.

Spooner's writings include the abolitionist book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery and No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority, which opposed treason charges against secessionists. Spooner is also known for competing with the Post Office with his American Letter Mail Company. However, it was closed after legal problems with the federal government.

Biography

Early life

Spooner was born on a farm in Athol, Massachusetts on 19 January, 1808. Spooner's parents were Asa and Dolly Spooner. One of his ancestors, William Spooner, arrived in Plymouth in 1637. Lysander was the second of nine children. His father was a deist and it has been speculated that he purposely named his two older sons Leander and Lysander after pagan and Spartan heroes, respectively.

Legal career

Spooner's activism began with his career as a lawyer, which itself violated Massachusetts law. Spooner had studied law under the prominent lawyers, politicians and abolitionists John Davis, later Governor of Massachusetts and Senator; and Charles Allen, state senator and Representative from the Free Soil Party. However, he never attended college. According to the laws of the state, college graduates were required to study with an attorney for three years while non-graduates like Lysander would be required to do so for five years.

With the encouragement from his legal mentors, Spooner set up his practice in Worcester, Massachusetts, after only three years, defying the courts. He regarded three-year privilege for college graduates as a state-sponsored discrimination against the poor and also providing a monopoly income to those who met the requirements. He argued that "no one has yet ever dared advocate, in direct terms, so monstrous a principle as that the rich ought to be protected by law from the competition of the poor"1. In 1836, the legislature abolished the restriction. He opposed all licensing requirements for lawyers, doctors or anyone else that was prevented from being employed by such requirements. For Spooner, to prevent a person from doing business with a person without a professional license was a violation of the natural right to contract. Spooner advocated natural law, or what he called the science of justice, wherein acts of initiatory coercion against individuals and their property, including taxation, were considered criminal because they were immoral, while the so-called criminal acts that violated only man-made arbitrary legislation were not necessarily criminal.

After a disappointing legal career and a failed career in real estate speculation in Ohio, Spooner returned to his father's farm in 1840.

American Letter Mail Company

Being an advocate of self-employment and opponent of government regulation of business, in 1844 Spooner started the American Letter Mail Company, which competed with the United States Post Office, whose rates were very high. It had offices in various cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York City. Stamps could be purchased and then attached to letters, which could be brought to any of its offices. From here, agents were dispatched who traveled on railroads and steamboats and carried the letters in handbags. Letters were transferred to messengers in the cities along the routes, who then delivered the letters to the addressees. This was a challenge to the Post Office's legal monopoly.

As he had done when challenging the rules of the Massachusetts Bar Association, Spooner published a pamphlet titled "The Unconstitutionality of the Laws of Congress Prohibiting Private Mails". Although Spooner had finally found commercial success with his mail company, legal challenges by the government eventually exhausted his financial resources. A law enacted in 1851 that strengthened the federal government's monopoly finally put him out of business. The legacy of Spooner's challenge to the postal service was the reduction in letter postage from 5¢ to 3¢, in response to the competition his company provided which lasted until late 1950's or early 1960's.

Abolitionism

Spooner attained his highest profile as a figure in the abolitionist movement. His book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, published in 1845, contributed to a controversy among abolitionists over whether the Constitution supported the institution of slavery. The disunionist faction led by William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips argued that the Constitution legally recognized and enforced the oppression of slaves as in the provisions for the capture of fugitive slaves in Article IV, Section 2. More generally, Phillips disputed Spooner's notion that any unjust law should be held legally void by judges.

Spooner challenged the claim that the text of the Constitution permitted slavery. Although he recognized that the Founding Fathers had probably not intended to outlaw slavery when writing the Constitution, Spooner argued that only the meaning of the text, not the private intentions of its writers, was enforceable. He used a complex system of legal and natural law arguments to show that the clauses usually interpreted as supporting slavery did not in fact support it and that several clauses of the Constitution prohibited the states from establishing slavery. Both the above discounted reality that slavery was in place before the Constitution was ever ratified and framers were forced to use compromise with existence of established investments whether those were illegal or not to gain its ratification. Spooner's arguments were cited by other pro-Constitution abolitionists such as Gerrit Smith and the Liberty Party, the twenty-second plank of whose 1849 platform praised Spooner's book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery. Frederick Douglass, originally a Garrisonian disunionist, later came to accept the pro-Constitution position and cited Spooner's arguments to explain his change of mind.

From the publication of this book until 1861, Spooner actively campaigned against slavery. He published subsequent pamphlets on jury nullification and other legal defenses for escaped slaves, and offered his legal services to fugitives, often free of charge. In the late 1850s, copies of his book were distributed to members of Congress. Even Senator Albert G. Brown of Mississippi, a slavery proponent, praised the argument's intellectual rigor and conceded it was the most formidable legal challenge he had seen from the abolitionists to date. In 1858, Spooner circulated a "Plan for the Abolition of Slavery", calling for the use of guerrilla warfare against slaveholders by black slaves and non-slaveholding free Southerners, with aid from Northern abolitionists. Spooner also "conspir[ed] with John Brown to promote a servile insurrection in the South"2 and participated in an aborted plot to free Brown after his capture following the failed raid on Harper's Ferry, Virginia (now part of the state of West Virginia).

Although he had advocated the use of violence to abolish slavery, Spooner denounced the Republicans' use of violence to prevent the Southern states from seceding during the American Civil War. He published several letters and pamphlets about the war, arguing that the Republican objective was not to eradicate slavery, but rather to preserve the Union by force. He blamed the bloodshed on Republican political leaders such as Secretary of State William H. Seward and Senator Charles Sumner, who often criticized slavery yet would not attack it on a constitutional basis, and who pursued military policies Spooner described as vengeful and abusive.

While denouncing the institution of slavery, Spooner recognized the right of the Confederate States of America to secede as the manifestation of government by consent, a constitutional and legal principle fundamental to Spooner's philosophy. In contrast, the Northern states were trying to deny the Southerners that right through military force. He vociferously opposed the Civil War, arguing that it violated the right of the Southern states to secede from a Union that no longer represented them. He believed the Northern States were attempting to restore the Southern states to the Union against the wishes of Southerners. He argued that the right of the states to secede derives from the natural right of slaves to be free. This argument was unpopular both in the North and in the South after the Civil War began, as it conflicted with the official position of both governments.

Later life and death

Spooner continued to write and publish extensively during the decades following Reconstruction, producing works such as his essay "Natural Law or the Science of Justice" and the short book Trial by Jury. In Trial by Jury, he defended the doctrine of jury nullification which holds that in a free society a trial jury not only has the authority to rule on the facts of the case, but also on the legitimacy of the law under which the case is tried. This doctrine would further allow juries to refuse to convict if they regard the law by which they are asked to convict as illegitimate. Spooner became associated with Benjamin Tucker's American individualist anarchist journal Liberty which published all of his later works in serial format and for which he wrote several editorial columns on current events.

Spooner argued that "almost all fortunes are made out of the capital and labor of other men than those who realize them. Indeed, large fortunes could rarely be made at all by one individual, except by his sponging capital and labor from others"3. Spooner defended the Millerites, who stopped working because they believed the world would soon end and were arrested for vagrancy.

Spooner spent much time in the Boston Athenæum. He died on 14 May 1887, at the age of 79 in his nearby residence at 109 Myrtle Street, Boston. He never married and had no children. Tucker arranged his funeral service and wrote a "loving obituary" entitled "Our Nestor Taken From Us" which appeared in Liberty on 28 May and predicted "that the name Lysander Spooner would be 'henceforth memorable among men'".

Political views

Anarchist George Woodcock, among others, described Spooner's essays as an "eloquent elaboration" of American anarchist Josiah Warren and the early American development of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's mutualist ideas and associates his works with that of American individualist anarchist Stephen Pearl Andrews. Woodcock also reports that both Spooner and William Batchelder Greene had been members of the socialist First International. According to Peter Marshall, "the egalitarian implications of traditional individualist anarchists" such as Spooner and Benjamin Tucker have been overlooked.

Spooner was an advocate for absolute property rights based on Lockean principles of initial acquisition. He wrote:

The right of property, therefore, is a right of absolute dominion over a commodity, whether the owner wish to retain it in his own actual possession and use, or not. It is a right to forbid others to use it, without his consent. If it were not so, men could never sell, rent, or give away those commodities, which they do not themselves wish to keep or use; but would lose their right of property in them—that is, their right of dominion over them—the moment they suspended their personal possession and use of them.4

As an individualist anarchist, Spooner advocated for pre-industrial living in communities of small property holders so that they could pursue life, liberty, happiness and property in mutual honesty without ceding responsibility to a central government. Spooner felt that an expansive government created virtual slaves and its demands of obedience expropriated the role of the individual. By letting the government make and enforce laws, Spooner contended that Americans "have surrendered their liberties unreservedly into the hands of the government"5. In addition to his extra-governmental post service and views on abolitionism, Spooner wrote No Treason in which he contends that the Constitution is neither a contract nor a text to which citizens are bound. Spooner argued that the national Congress should dissolve and let citizens rule themselves as he held that individuals should make their own fates.

Spooner believed that it was beneficial for people to be self-employed so that they could enjoy the full benefits of their labor rather than having to share them with an employer. He argued that various forms of government intervention in the free market made it difficult for people to start their own businesses. For one, he believed that laws against high interest rates, or usury, prevented those with capital from extending credit because they could not be compensated for high risks of not being repaid, writing:

If a man have not capital of his own, upon which to bestow his labor, it is necessary that he be allowed to obtain it on credit. And in order that he may be able to obtain it on credit, it is necessary that he be allowed to contract for such a rate of interest as will induce a man, having surplus capital, to loan it to him; for the capitalist cannot, consistently with natural law, be compelled to loan his capital against his will. All legislative restraints upon the rate of interest, are, therefore, nothing less than arbitrary and tyrannical restraints upon a man's natural capacity amid natural right to hire capital, upon which to bestow his labor. ... The effect of usury laws, then, is to give a monopoly of the right of borrowing money, to those few, who can offer the most approved security.6

Spooner believed that government restrictions on issuance of private money made it inordinately difficult for individuals to obtain the capital on credit to start their own businesses, thereby putting them in a situation where a "very large portion of them, to save themselves from starvation, have no alternative but to sell their labor to others" and those who do employ others are only able to afford to pay "far below what the laborers could produce, [than] if they themselves had the necessary capital to work with"7. Spooner said that there was "a prohibitory tax–a tax of ten per cent.–on all notes issued for circulation as money, other than the notes of the United States and the national banks"8 which he argued caused an artificial shortage of credit and that eliminating this tax would result in making plenty of money available for lending.

Spooner was opposed to wage labor, arguing: "All the great establishments, of every kind, now in the hands of a few proprietors, but employing a great number of wage laborers, would be broken up; for few or no persons, who could hire capital and do business for themselves would consent to labor for wages for another"9. In response to anarcho-capitalists arguing that Spooner was a right-libertarian and anarcho-capitalist, Iain MacSaorsa argues that because Spooner was opposed to wage labor, he was a socialist of a particular kind, particularly market socialism, since capitalism is not the only market system. Spooner's membership to the socialist First International and opposition to wage labor is why the authors of "An Anarchist FAQ" and anarchist historians such as James J. Martin and Peter Marshall consider him an anti-capitalist left-libertarian, libertarian socialist, and market socialist. Others have referred to Spooner as a libertarian, an anarcho-capitalist, and a propertarianist.

Influence

Spooner's influence extends to the wide range of topics he addressed during his lifetime. He is remembered primarily for his abolitionist activities and for his challenge to the Post Office monopoly which had a lasting influence of significantly reducing postal rates, according to the Journal of Libertarian Studies.

Spooner's writings were a major influence on Austrian School economist Murray Rothbard and libertarian law professor and legal theorist Randy Barnett. His writings were often reprinted in early libertarian journals such as the Rampart Journal and Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought. While influencing anarcho-capitalists such as Rothbard, MacSaorsa argues that Spooner was an "anti-capitalist" who preferred to see "a society of self-employed farmers, artisans and cooperating workers, not a society of wage slaves and capitalists". MacSaorsa further argues that Spooner was opposed to wage labor, "wanting that social relationship destroyed by turning capital over to those who work in it, as associated producers and not as wage slaves".

In January 2004, Laissez Faire Books established the Lysander Spooner Award for advancing the literature of liberty. The honor was awarded monthly to the most important contributions to libertarian literature, followed by an annual award to the winner. In 2010, the Libertarian, Agorist, Voluntaryist and Anarch Authors and Publishers Association (LAVA) created the Lysander Spooner Award for Book of the Year.

Spooner's The Unconstitutionality of Slavery was cited in the 2008 Supreme Court case District of Columbia v. Heller which struck down the federal district's ban on handguns. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the court, quoted Spooner as saying the right to bear arms was necessary for those who wanted to take a stand against slavery. It was also cited by Justice Clarence Thomas in his concurring opinion in McDonald v. City of Chicago, another firearms case, the following year.

-

"To the Members of the Legislature of Massachusetts", Worcester Republican, 26 August 1835. ↩︎

-

Ralph Raico, Great Wars and Great Leaders: A Libertarian Rebuttal, Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2010, pp. viii-ix. ↩︎

-

Poverty: Its Illegal Causes and Legal Cure, Part First, Boston: Bela Marsh, 1846, p. 11. ↩︎

-

The Law of Intellectual Property, Boston: Bela Marsh, 1855, Vol. I, pp. 82-83. ↩︎

-

An Essay on the Trial by Jury, Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1852, p. 12. ↩︎

-

Poverty, op. cit., pp. 8-9. ↩︎

-

A Letter to Grover Cleveland, Boston: Benj. R. Tucker, 1886, p. 39. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 74. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 41. ↩︎

This article is derived from the English Wikipedia article "Lysander Spooner" as of 6 Feb 2022, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.